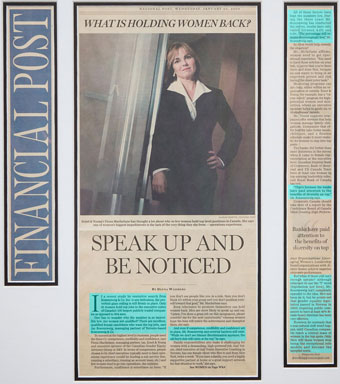

Ernst & Young's Fiona Macfarlane has thought a lot of why so few woman hold top level positions.

If a recent study by executive search firm Rosenzweig & Co. Inc. is any indication, the proverbial glass ceiling is still firmly in place. Only 31 women hold top jobs in the executive suites of Canada's 100 largest publicly traded companies as opposed to 504 men.

One has to wonder why the number is so incredibly low. Are women not qualified? There are excellent, qualified female candidates who want the top jobs, says Jay Rosenzweig, managing partner of Toronto-based Rosenzweig & Co.

To succeed at the highest level in business, people need the three Cs: competence, credibility and confidence, says Fiona Macfarlane, managing partner, tax, Ernst & Young and executive sponsor of the Canadian Gender Equity Advisory Group at E&Y. In terms of competence, people chosen to be chief executives typically need to have operations experience (could be leading a sub-service line, running a subsidiary, running an account team, etc.) and few women tend to go into operations, she explains.

Furthermore, confidence is sometimes an issue. "If you don't see people like you in a role, then you don't think it's within your grasp and you don't position yourself toward that goal," Ms. Macfarlane says.

Even reluctance to promote themselves can hold women back. Men are more likely to speak up and say, "Listen, I've done a great job on this assignment, please consider me for the next opportunity," whereas women hope the boss will notice the achievement and champion them, she says.

And even if competence, credibility and confidence are in place, Mr. Rosenzweig says societal barriers still exist. "While we don't see blatant discrimination anymore, the old boy's club still exists at the top," he says.

Family responsibilities also make it challenging for women with a demanding, high-powered job. Gail Voisin, chief executive of Gail Voisin Executive Coaching in Toronto, has one female client who flies to and from New York, twice a week. "If you have a family, you need a highly supportive partner at home or a great support network for that situation to work," she says.

All of these factors have kept the numbers low. During the three years Mr. Rosenzweig has conducted the survey, results have only varied between 4.6% and 6.9%. "The percentage still remains discouragingly low," Mr. Rosenzweig says.

So what would help remedy the situation?

Ms. Macfarlane affirms, women need to get operational experience. "You need to have those notches on your belt, to prove that you've been there and done that, because no one wants to bring in an unproven person and risk having the share price tank."

Mentoring programs can also help, either within an organization or outside. Ernst & Young, for example, has a "career watch" program for high-potential women and minorities, where an executive member helps to guide six to 10 employees' careers.

Ms. Voisin suggests companies offer services that help women manage family obligations. Companies that offer healthy take-home meals, childcare, and a flexible schedule make it more realistic for women to step into top posts.

The banks did better than most industries in the survey when it came to female representation at the executive level. Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, Bank of Montreal and TD Canada Trust have at least one woman in top-earning leadership roles, and Royal Bank of Canada has two.

"That's because the banks have paid attention to the benefits of diversity on top," Mr. Rosenzweig says.

Corporate Canada should take note of a report by the Conference Board of Canada titled Creating High Performance Organizations: Leveraging Women's Leadership found organizations with diverse teams achieve superior corporate performance.

But what if there still isn't enough uptake? Although reluctant to use the "l" word (legislation not love), Mr. Rosenzweig isn't completely opposed to the idea. He's not keen on it, but he points out that gender equality legislation passed in Norway in 2003, requiring public companies to have at least 40% female board directors has been very effective.

However, he contends that a real cultural shift won't happen until Canadian companies reach a critical mass of women in the top spots. Only then will these women stop being the exceptional role models and become the accepted norm.